By Larry Rohter | Published: Monday, November 15, 1993

Rebuffing their Governor and his efforts to make this Caribbean island commonwealth the 51st state, Puerto Ricans voted narrowly today to continue their existing ambiguous relationship with the United States.

By choosing to maintain the commonwealth status that has been in place here for more than 40 years, Puerto Ricans made it clear that they prefer “the best of two worlds,” in the words of a pro-commonwealth campaign slogan, to the prospect of more intimate ties with the United States. By an overwhelming margin, they also rejected independence, the third option that had been offered to them in the nonbinding vote today.

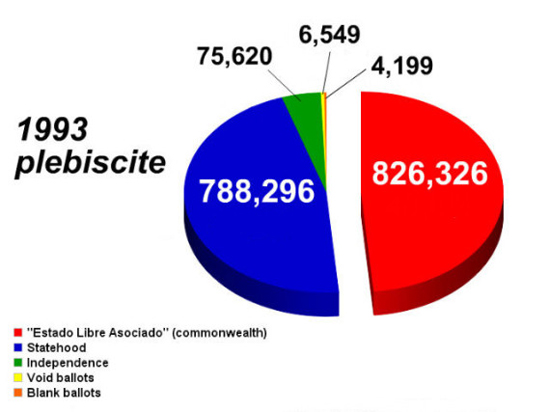

With all votes counted, the commonwealth option won 48 percent of the vote, compared with 46 percent for statehood. Independence accounted for about 4 percent of the vote, with a small number of ballots being deliberately cast blank or spoiled as a protest against the plebiscite. Problems of Statehood

“Commonwealth is the formula that is most convenient for Puerto Rico,” said Angel Casanova, a 52-year-old woodworker, after voting this morning in Bayamon, a San Juan suburb. “Statehood would only result in more problems.”

Gov. Pedro Rossello acknowledged the defeat in a speech at the headquarters of his New Progressive Party a few hours after the voting ended this afternoon. “The people have spoken, and I have to obey,” he said. He added that by turning out in large numbers and peacefully exercising their right to vote, “in the eyes of the whole world the people of Puerto Rico have shown their class and their commitment to democracy.” A Majority for Neither

Nevertheless, the result threatens to usher in a period of political uncertainty here and change Puerto Rico’s relations with Washington. Thanks to the showing of the Puerto Rico Independence Party, neither of the two main parties here can claim to represent a majority of the island’s 3.7 million people.

In addition, Mr. Rossello and Puerto Rico’s non-voting delegate to Congress, Carlos Romero-Barcelo, will now be expected to ask Washington to enhance Puerto Rico’s existing commonwealth status after having spent the last three months attacking the status quo as a “shameful” remnant of colonialism.

Tonight, leaders of the pro-commonwealth Popular Democratic Party called on Mr. Rossello to begin discussions with them over how those enhancements should be pursued in Washington.

Since 1952, Puerto Rico has been a commonwealth of the United States, a unique arrangement that gives the residents of Puerto Rico some, but not all, of the rights and responsibilities of American citizenship. With commonwealth status, Puerto Ricans are subject to the military draft, but do not vote in Federal elections and do not pay Federal taxes so long as they live here.

An additional 2.6 million Puerto Ricans live on the American mainland and are treated like all other citizens. Mr. Rossello, who campaigned on a statehood platform when he won office a year ago, had made that one of his main arguments for statehood, saying it was time to end Puerto Rico’s “second class” status.

The Popular Democratic Party, in contrast, offered a slightly modified version of commonwealth. They vowed to seek restoration of tax benefits that Congress reduced earlier this year to cut the Federal budget deficit. The party also said it would fight for an increase in Federal aid to the elderly, the disabled and the poor.

Throughout the campaign, backers of commonwealth status also argued that statehood would require Puerto Rico to relinquish both its use of the Spanish language and its cultural identity. They also said that statehood would bring with it a Federal income and increased Federal levies on gasoline, cigarettes and liquor.

Though three former Republican Presidents had urged voters here to choose statehood, President Clinton remained neutral during the campaign, saying only that he would respect the will of Puerto Rico’s people. “Whatever they want, I want,” Mr. Clinton told the Congressional Hispanic Caucus in September.

What voters apparently did not want was a substantial change, said Representative Jose Serrano, Democrat of the Bronx, who is one of three Puerto Ricans in Congress.

But Mr. Serrano, who did not take a public position on the issue, added: “I question how long we can keep this kind of relationship. Essentially, we have a colony in the Caribbean. We go around the world talking about democracy but we still have a colony. Eventually it’s going to be a problem for us.” Sparing Congress

Still, the result of the vote spares Congress the difficult and controversial decision that would have confronted it had Mr. Rossello’s party been successful: whether to grant or reject statehood for Puerto Rico. Privately, many members of Congress say they are content with the current relationship and are reluctant to tinker with it.

At a news conference Saturday night and in his speech tonight, Mr. Rossello, a 49-year-old pediatric surgeon, gave no timetable for submitting the “enhanced commonwealth” program to Congress for approval. But he did give one indication of the political difficulties that may lie ahead for the island. He said that since the Popular Democratic Party, which controls neither the commonwealth government nor Puerto Rico’s representative in Washington, had offered the winning option in the vote, “it is up to them to keep their word with the people of Puerto Rico.”

The plebiscite on Puerto Rico’s political status was the first since 1967, when commonwealth won 60 percent of 700,000 votes cast, compared with 39 percent for statehood. The Puerto Rico Independence Party had urged a boycott of that vote, and independence was favored by fewer than one percent of voters. Heavy Turnout

The last series of public opinion polls taken before the vote today had shown statehood and commonwealth in a virtual tie, with each supported by about 40 percent of voters surveyed. Leaders of both parties were predicting that victory would go to whichever side did the best job in bringing its supporters to the polls.

Turnout for the vote today was higher than in the 1967 plebiscite, when just under two-thirds of registered voters cast ballots. Members of the State Electoral Commission estimated that more than 73 percent of Puerto Rico’s 2.2 million voters voted today, a sign of the passions aroused by the issue.

Despite rain that began at mid-morning and continued until the polls closed at 3 P.M. local time, the mood across the island was one of celebration. Cars bearing oversized American flags or the banners of the two main parties raced through the streets during the day and into the evening, their horns tooting and their passengers leaning out the windows to chant political slogans.

At polling places, 5,611 of which were set up at schools around the island, election judges good-naturedly kidded each other about their parties’ chances; there were no immediate complaints of voting irregularities. Once the polls closed, supporters of the three options flocked to their respective party headquarters to hear the results come in, dancing, singing, and eating in the 85-degree heat as they waited for the tabulations to be posted.

At one polling place in Carolina, another San Juan suburb, an ambulance drove up around midday, and election officials carried an elderly voter to the booth so that he could vote. Radio stations carried reports of commonwealth party volunteers in many areas ferrying elderly or infirm sympathizers to the polls so they could vote for the status quo.

“I have no doubt the success we are enjoying now is the result of that effort by our members,” said Celeste Benitez, director of the commonwealth campaign. She added that “statehooders received a tremendous setback, especially when you consider the economic resources they had at their disposal.” Lesser of Two Evils

But the commonwealth total apparently was also swelled by the adherence of some voters who had declared themselves in favor of independence. Faced with the possibility of Puerto Rico entering the union, they opted for the lesser of what they viewed as two evils.

“In my heart, I’ve always been for independence,” said Carlos Fuentes, a 29-year-old teacher in Carolina. “But the strong campaign effort and ad campaign of the statehooders left me in sort of a panic, and so I voted for commonwealth to make sure that statehood would not win.”

At the same time, many voters who last November cast their ballots for Mr. Rossello and the New Progressive Party, giving them control of two-thirds of the island’s municipalities, switched parties this time. They made it clear that though they were not critical of Mr. Rossello’s performance, they simply could not commit themselves to the drastic change in Puerto Rico’s political status that he was advocating.

“I always look for the best candidate, and I thought that was Rossello,” said Jorge Valcarcel, a resident of Caguas, about 20 miles south of the capital. “But I believe in commonwealth, and that’s what I voted for.” RETHINKING PUERTO RICO, POLITICALLY

In Sunday’s nonbinding plebiscite, Puerto Rico grappled again with whether to remain a commonwealth of the United States, to become the 51st state or to become an independent nation. Political History Puerto Rico became a United States territory in 1898, after the Spanish-American War. It was ruled by a presidentially appointed governor until 1947, when Congress voted to allow Puerto Ricans to elect their own governor. Since 1900, the island has been represented in the United States Congress by a nonvoting, locally elected resident commissioner. The commissioner has a four-year term. Puerto Ricans became United States citizens in 1917, but they cannot vote for President, are exempt from Federal taxes and get limited Federal aid. Commonwealth In 1952 the current Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico was drafted by its elected Constituent Assembly, approved in referendum by 80 percent of voters and ratified by the United States Congress. As a Commonwealth, Puerto Rico is part of the United States for purposes of international trade, foreign policy and war (including military service), but has its own laws, taxes and representative government. In a plebiscite in 1967, 60.5 percent of voters were in favor of improved commonwealth status rather than statehood or independence. Population Puerto Rico is home to 3.7 million people, of whom 2.3 million are registered voters. The 2.6 million Puerto Ricans living on the United States mainland could not vote in Sunday’s plebiscite. Economy The island’s annual per capita income in 1989 was $6,200, the highest in Latin America but about half that of the United States mainland. Many manufacturing jobs, notably in pharmaceuticals, depend on Section 936 of the Internal Revenue Code, which shelters profits made in Puerto Rico from Federal taxes.