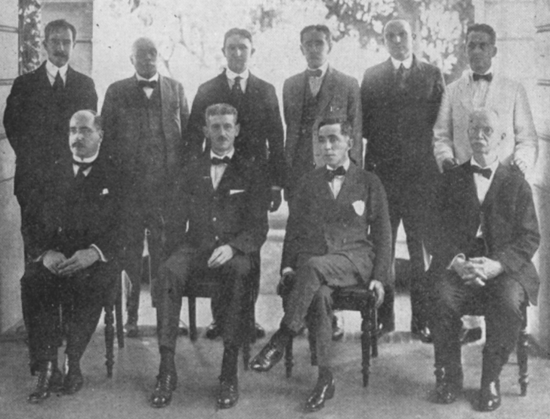

First administrative cabinet under the Jones Act. From left: A. Ruíz Soler (Health), José E. Benedicto (Treasurer), Ramón Siaca Pacheco (Secretary), Hon. Arthur Yager (Governor, 1914-1921), Paul G. Miller (Education), Manuel Camuñas (Labor and Agriculture), Salvador Mestre (Attorney General), Guillermo Esteves (Interior), Jesse W. Bonner (Auditor), Pedro L. Rodríguez (Governor’s Secretary).

The Jones–Shafroth Act (1917) was a 1917 Act of the United States Congress by which, Puerto Ricans were collectively made U.S. citizens, the people of Puerto Rico were empowered to have a popularly-elected Senate, established a bill of rights, and authorized the election of a Resident Commissioner to a four year term. Also known as the “Jones Act of Puerto Rico” or “Jones Law of Puerto Rico”, it amended the “Organic Act of Puerto Rico” created by the Foraker Act of 1900. (This “Jones Act” applies only to Puerto Rico.) The act was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on March 2, 1917

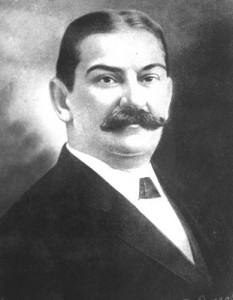

Luis Munoz Rivera

The impetus for this legislation came from a complex of both local and mainland interests. Puerto Ricans lacked internationally recognized citizenship; but the local council was wary of “imposing citizenship.” Luis Munoz Rivera, The Resident Commissioner in Washington, argued in its favor, giving several significant speeches in the House of Representatives. On 5 May 1916 he demanded: “Give us now the field of experiment which we ask of you. . . . It is easy for us to set up a stable republican government with all possible guarantees for all possible interests. And afterwards, when you . . . give us our independence . . . you will stand before humanity as a great creator of new nationalities and a great liberator of oppressed people.”

The Act made all citizens of Puerto Rico U.S. citizens collectively and revised the system of government in Puerto Rico. In some respects, the governmental structure paralleled that of a state of the United States. Powers were separated among an Executive, Judicial, and Legislative branch. The law also recognized certain civil rights through a bill of rights to be observed by the government of Puerto Rico (although trial by jury, which did not exist in Puerto Rico’s civil law system, was not among them).

When the Selective Service Act of 1917 was passed two months later, it allowed conscription to be extended to the island. Some 20,000 Puerto Rican soldiers were sent to World War I. Before the Act was signed, Puerto Ricans residents of the island who were not citizens of the United States (their citizenship since 1898 was Puerto Rican) were considered as aliens. But then Isabel Gonzalez arrived in New York from Puerto Rico. US Immigration attempted to deport her back to Puerto Rico, but she appealed her case up to the Supreme Court and won immigration rights for all Puerto Ricans from that point forward. However, the Court fell just short of granting US Citizenship status. As such Puerto Ricans were ineligible for the draft. Prior to the Act, Puerto Ricans in the mainland United States who were permanent residents were required to register with the Selective Service System and could be drafted

Portions of the Jones Act were superseded in 1948, after which the Governor was popularly elected. In 1948, U.S. Congress allowed Puerto Rico to draft its own Constitution which, when implemented in 1952, provided greater autonomy as a Commonwealth